| Transcribed and researched by Janet Meads 2007 |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

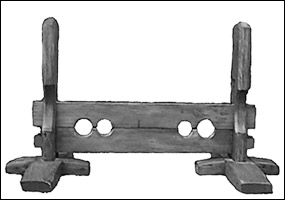

In the early 17th century the king's government was of little direct concern to the townspeople of Burton Latimer; any matters relating to government were dealt with by senior local officials: lord lieutenants, sheriffs, and justices of the peace of the county. Overseers of the poor, surveyors of highways, and churchwardens were the officials that the local community knew and dealt with, as these were men from their own parish and were elected locally. Although the main offices were usually held by the landed gentry, farmers, tradesmen and craftsmen were expected to hold the lesser local government posts. During the early 17th century the constable was elected at the Manor Court and usually held the post for that year. During that year he had to pay out cash for various purposes and, to obtain that money, he could impose levies or taxes on the local inhabitants. At the end of the year he had to account for the money he had received and spent. These accounts for the years 1633 to 1640 for Burton Latimer, which are deposited in the County Record Office, are very detailed and give an excellent idea of the life in the village at that time. Other constable's accounts survive but are not as detailed, which is why these years have been chosen as an example. The constable could claim expenses but had no wage, which meant he usually continued with his regular occupation at the same time, this was possible as there does not seem to be too much serious crime in Burton Latimer during these years. The constable's year of office started and ended at the Manor Court, which was sometimes held in Burton Latimer but could be held locally elsewhere. The newly to-be-sworn constable and the constable who had served his year, had to hire a horse each to take them to the court if it was out of the village. From the accounts it is obvious that most people did not own their own transport, whenever business had to be conducted out of town, a horse or horse and cart, had to be hired to get them to the place of business. The constable's duties were many and varied. They included, for instance, making sure that the soldiers serving in the militia were well trained and their equipment in good order, buying a brass kettle to brand the town beasts before they went out on to the common ground and buying a new whipping post and getting it set up at the Cross. At the Manor Courts, certain local laws were established with regard to the common lands in the parish and these laws would have been overseen by the constable. Although no examples seem to have survived for 1634 -40, in 1708 the jury at the court imposed four new local laws. 1. "That no cows shall go in the meadows after St. Thomas untill they are broke up except upon their own ground." 2. That no persons shall gather dung off the land or pasture, inclosed or common ground within the Parish of Burton under the penalty of two shillings and six pence for every defaulte." 3. "That no hog shall go in the ffield above three weeks after harvest is in without they are ringed, under the penalty of two pence a hog." 4. "That no person shall carry straw or furze or make any new highways over the common inclosed or pasture ground within the said Parrish." These byelaws would have been controlled by the constable of that time, just as similar byelaws would have been controlled during 1634 and 1640. In 1638 the constable had to return a warrant to Kettering for "binding the alehousekeepers from dressing and eating venison, pheasants and pootes (poultry) in there houses unles the same be of thiere owne breeding." In other words not bought from a poacher. The only way a village or town could provide for its poor was by taxing the other members of its community, in the 17th century no governmental help was available. Any money that was needed for the poor or for village maintenance was provided by the better-off people in the village through a levy which was worked out by calculating how much land each person held. The rate for each levy varied depending on how much the constable needed to pay out, but it was usually between 8d and 1s for each yardland that the villager owned and a levy could be imposed more than once a year. Obviously, the poorer members of the community did not pay anything. If a villager fell on hard times it was expected that the parish would look after them, either by providing them with food from one of the local charities, or some kind of suitable work. A couple of men were elected to be stone reeves and it was their job to get poor members of the community with no full time occupation, to collect stones lying in the fields and put them to a better use, like filling in holes in the roads, the reeves would then provide the workers with some food and drink. In 1635 3s 4d was given to the stone reeves to be expended upon the stone gatherers but in 1638 the accounts record "Laid out by John Hunt and Thomas Mason stone reeves in bread and drinck amongst the stone gatherers whereof many were pore people and children of the towne (bread and drinck being very smalle in regarde of the yeres scarsitie) 6s 8d." Handouts were not easily come by. If a newcomer to the village suddenly became ill or unable to work, that was an entirely different matter and that person was expected to return to their original birthplace. A family moving into the parish could bring a settlement certificate from their original parish which would state that their parish of birth would either take them back or would pay for any costs incurred by their new place of settlement, should that be necessary. Often people moved some distance from their place of birth during their lives, for family reasons, marriage or work and should they fall on hard times, these people had to make the often long journey back to their original parish, even though they were sometimes very sick. It was the constable's duty to meet these people at the parish boundary and escort them through the town or village to the next boundary, where they would be passed on to the next constable. If they had a pass and it was night time the constable would arrange sleeping accommodation for the traveller or, if during the day, a small amount of money for some food to send them on their way. For sick people, transport from one parish boundary to another had to be provided. Burton Latimer seems to have been a regular route for these travellers and a small sample are quoted:- To a poore boy with a passe 1d. To a pore boy goeing to London 2d. To 4 pore Irish people who had losse by sea 6d. To a nother pore body 1d. Given to Onell Mac, his wife and 2 other Irish vagrantes whoe were whipt and sent by Passe to Westchester to Divelyn in Ireland 6d. To 11 Gipsies with a passe from Cranford to Thingdon [Finedon] to Ruck in Cumberland taken up at St Albones 10d. Given to Fletcher of Rothwell being visited in the Fenns with an Ague and brought unto us from Thingdon in a carte 6d. For the hyre of Glover's horse of Thingdon to convey the said Fletcher to Barton in respect our neighbors were all busied about their hay 6d. To Elizabeth Scott a Sutler in Stephen Bergen in Brabant and 4 children who had her husband killed by the Spanyards and her hose and yards fyred by the enemye having a passe from the Mayor of Westchester to Dover to her frindes there 10d. Allowed to Alehousekeepers Shrive and Arch our two Alehousekeepers for theire straw which have bene used for this yere past about lodging of criples and other vagrantes whome wee have brought into them viz. 6d a peece 1s 0d.

What sad story lies behind the line in the accounts which reads:- To a pore wench who was found nere Isham planck sick and almost starved 4d. If by any chance a young woman was found to be pregnant in the village without being married or having any means of support, every effort was made to find and force the man to marry her. If she was of another parish she was soon dispatched to her original birthplace or the place where she might be able to identify the man responsible for her predicament, as with Margerie Walter in 1634 and Mary Cooper in 1638:- Paid for a warrant for Margerie Walter to convey her awaie being gotten with childe at Wellingborow 6d. For a horse hyer to carrie her 12d. For a mans wages to goe with her 6d. To Isack Phillipps for goeing to Northampton with Mary Cooper gott with childe there being sent hither by the constables of Ecton 1s. For a warrant for the said Mary Cooper 6d.

The constable was also responsible for making sure that the maintenance of the highways, waterways and bridges in the parish was carried out. In 1633 it was necessary for work to be done on the River Ise running to the west of the village:- For hyring of divers laborors for the making and finishing of the new dike to carrie the meadow water from the trough at Woollstubs meadow all a long to the backside of Southmill 8s 10d. For a tymber stick to make the said trough 11s 0d. For other tymber used about the grate thereof 8s 0d. For tallow pitch and tarr for ye same trough 6d. To the carpenters for the making thereof 7s 0d.

This is quite an expensive outlay when a levy usually brought in between £13 and £14 and had to be used for many other things. There are several more references to work carried out on the river as will be shown later. Then the road leading from Burton Latimer to Isham was in need of repair:- For stone to mend the waie at Northmill 3s 0d. For carriage thereof 1s 6d. To the laborors for the laying thereof 10d. This last item might have been paid for beer or something similar for refreshment for the labourers, as it seems very little for such hard work.

Several times the constable had to make sure that the roads running through the village were well maintained. The villagers were quite prepared to throw their rubbish out of their houses or dung from their animals onto the street, which could block the drains or watercourses, which would not have been culverted at this time:- Paid for 4 laborors to turne the snow water downe Mr Bacons Dike at Northe townes end to runne downe the water course through the Closses 3s 0d. Paid the mason for mending the bridge at the end of Medbornes gutter next the Cawsey in the street 2s 0d. For stone for the same 8d The first item probably refers to the shallow ditch that is still visible in the field to the south of the Hall ( the then home of Mr Bacon), which, until it was culverted, during the winter months, would still flood into the houses in the old Spring Gardens in Bakehouse Lane.

There were some criminal activities which involved the whole village. It is surprising to find that in 1638 a hue and cry was made in the night-time by the Burton Latimer constable because a thief had stolen 4 pairs of sheets, a carpet etc at Toft in Cambridgeshire. The hue and cry was sent westward going from one village to the next hoping that there would be some sighting of the thief, one would imagine that he would have gone to ground long before he reached this area. This is rather an extreme case of a hue and cry but there are several others recorded in the accounts:- For making of four hue and cryes to send east west north and south after a rogue one Giles Tompson whoe was whipped in our towne for taking Widdow Toothills petticoate off of the hedge, and was sent with a passe to Rothwell where he said he last dwelled. And in our feild gave Whitlarke our bedle a box on the eare and ran away from him 4d. For sending of a hue and crye in the night tyme for 3 cowes stolne from Stok Doyle 4d. For sending a hue and crie to Isham in the night tyme which came from Old Weston westward after one that had stolne a browne cowe stilted of both eares with the top of her horne sawne off with a calf 4d. For sending another hue and crie by James Basforde to Thingdon after Stephen Hutt for robbing of Mr Sawyers Mill 3d.

In 1640 a note appears in the margin of the accounts which states that no allowance will in future be made for sending out hue and cries.

Although not a lot of the king's government directly affected the village, when the king decided to recruit an exact militia there seems to be much activity shown in the accounts concerning the men who were trained soldiers in the village. The militia would have been similar to our present day territorial army, generally going about their everyday work but periodically going off to practice using the village armour and equipment. For practice at home the village provided butts, a high bank of soil with targets for shooting at. These were regularly repaired by digging a dike around the bank and placing new turf on the worn parts. The constable had to find money for these repairs and practices and had to make sure that the equipment was in working order, hence:-

1634 For carrying ye armor to Harrowdon to be dressed 8d For making the buttes 2s 0d For the armour dressing 4s 0d Laid out at Kettering uppon our trayned soldiours 9s 0d Paide there to the highe constable for soldiours pay 12s 0d For fetching the armor from the smiths at Harrowdon 8d For carrying the same to Kettering when they trayned 8d Paid John Mitchell the smith for certen work done at several tymes for the towne, viz. uppon his bill, first for dressing and mending the towne armor at two severall tymes 2s 6d For hyring of a horse to ride to Oundle to ye trayneing he being one of the trayne menn 1s 0d For making of a new rest for the muscott 6d There are several occasions when it is noted during 1634 that the butts had to be repaired. Perhaps the expense became too much for there is no mention of the soldiers training or the armour being repaired between 1635 and September 1638 when the account reads:- To James Dallicock an informer to stop his mouth from indicting the towne for not repairing the butts 1s 6d.

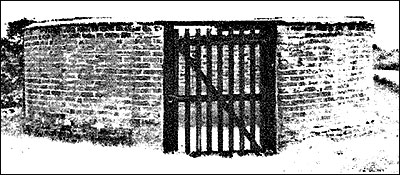

Then in 1638 the training at Kettering began in earnest once more and the armour was again transported and powder and match bought for the musket. Eventually in 1640 the constable paid 9d to have the town musket mended when it was broken. Another drain on the accounts was the upkeep of the pound. Animals were strictly limited to the area they could use and were only allowed in certain fields or pastures at certain times of the year. The manorial courts made byelaws which stated the times of the year when the animals could be let out on to the common fields. If by any chance a cow strayed from its owner's enclosure, then it was up to a villager to report it and it would be taken to the pound, where it would be locked in until the owner paid a fine to retrieve it. It is believed the Burton Latimer pound stood towards the far end of Meeting Lane, just beyond John Yeomans Hall. So that the owners of the sheep or cattle, confiscated in the pound, could not get their animals out when no-one was about, the pound had to be made secure:- For a broad stone to mend the bridge at the pounde 10d For a lock and two keys for the pound dore 7d For stone to mende the Common pound 1s 4d For mending the saide pounde 1s 10d Laid out uppon the masons when they had done the same 2d

Money that was collected in the village for various other taxes, had to be paid to officials when they visited the larger towns. The money had to be paid to the Clerk of the Market at Kettering; the Ship Money was another tax that had to be paid at Kettering (although several Burton people did not approve of it and did not pay until they were forced to). In 1634 St. Paul's Church in London was in a poor state and Indigo Jones was employed there to do repairs, the people of Burton gave money "freely" towards the repair and 6d was sent. Among other taxes, the sum of £2.2.8 had to be paid in at Kettering yearly for the king's provision and maimed soldiers. The king imposed several taxes on the ordinary people, including those in Burton Latimer, to provide money for his extravagant lifestyle. All these taxes were collected locally and then a horse had to be hired to take a man and the money to the collector, usually at Kettering but sometimes at Northampton or other places, which also incurred extra costs. As previously mentioned, the river between Isham and Burton was another item on the constable's accounts. It is obvious that it was important that the river was able to flow freely or the fields around would be subject to flooding, as they are today. The responsibility for the maintenance of the river and its banks was usually shared between the two villages, with both places providing workmen and money:- Candlemas1634 Paid to divers laborers of our towne for clensing and scowring the river of our owne side betwext Isham and us according to the Commissioners of Sewers warrant from Burton Northmill to the great stone bridge leading into Isham meadow after the rate of 2s 6d the acre between Isham men and us, so that our part or one half was 15d the acre, and there conteyned of acres for our part viz. £8 Imprimis Southmill Holme from Stone bridge to the whett meadow conteynes 27 acres. From the whett meadowe to Isham Sauffholme 16 acres. From Isham Sauffholme to the netherend of Preistholme 27 acres. Burton Sauffholme 17 acres. From the netherend of Preistholme to Swans Nest 7 acres. From Swans Nest to Northmill Netherfford 20 acres. Northmill Holme 14 acres. In toto 128 acres.

August 1638 To Roberte Chapman and Richard Arbor for mending the banckes of the wett meadow next the river 2s 4d

February 1638/9 Paid to Edward Wallis and the rest of the workemen for scowring of langcoorth dike being 16 acres at 11s 6d the acre, and for scowring and cutting the trough dike deeper and wider being 15 acres and a half above and below the trough viz. from the meadow dike to Southmille, at 20d the acre which comes to £3 10s. For earnest 2s 0d. For taking up the trough and laying it deeper by a foote and a half for the better conveying awaie of the meadow water 2s 0d For landing up of the old dike end next the river with the soile cut and throwne out of the said trough dike 5s 0d. At the end of the year, the constable employed one of the better educated villagers to write up all his accounts and this cost, usually about 3s 4d, was included in the final tally. The accounts would then be submitted for the villagers to view. In theory, any excess money or goods or even animals bought during the year, would be passed to the new constable. Any deficit would be reimbursed as soon as the next levy was collected. Many of the Burton Latimer constable's accounts are deposited at the Northamptonshire County Record Office and make fascinating reading. The above give only a small glimpse into the life of the village between 1634 and 1640. Click Here to read more extracts from the Burton Parish Constables' Accounts Click Here for further general information about Parish Constables |

||||||||||