| Feature researched and compiled by John Peck | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

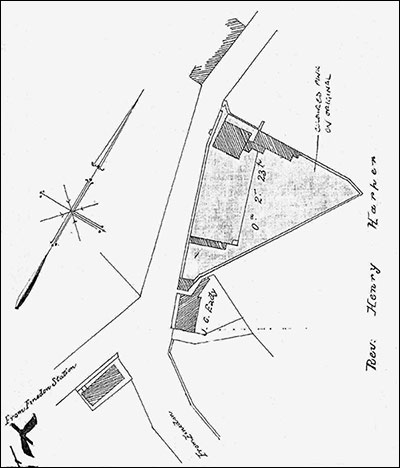

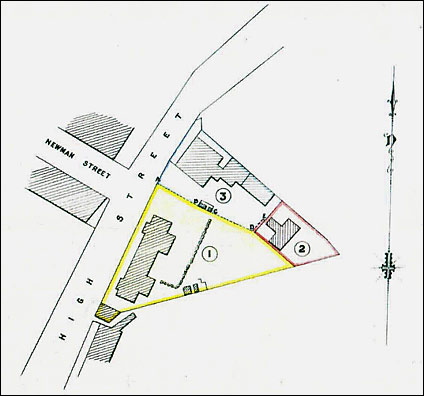

Following the Poor Law Act of 1834 many changes took place later in the century in the treatment of those in extreme poverty. Chief among these was the construction of numerous local workhouses, which as the name indicates were designed not only to accommodate paupers and often their families, but to provide manual work, whereby some of the cost of their keep might be offset. Indeed at Other important changes included the employment of full time staff. Whilst the opportunity for advancement and qualifications in the modern sense was very limited, in practice those in the more senior positions seemed to have stayed many years, often to retirement or to obtain a similar post in another locality. They clearly felt it to be their vocation. At junior levels however, particularly amongst nursing staff, a very high turnover and frequent serious understaffing were common, the matron and senior nurses covering the absences sometimes for weeks on end. The 1834 Act had provided that the Poor Law of the whole country be administered by several hundred “Unions” controlled by local “Guardians of the Poor”. These officials were elected in a similar fashion to local councillors and were unpaid. Meetings were held fortnightly throughout the year, attended normally by about twenty Guardians under an elected Chairman. The copious and detailed Minutes were recorded by the paid and professional Clerk, a local solicitor who would hold this highly respected appointment usually for many years. Whilst predominantly men were Guardians, by the end of the century a number of lady Guardians were making significant contributions to the work of the Guardians’ Committee particularly with respect to the needs of the elderly female workhouse inmates, the numerous children in the workhouse, and those “boarded out” with foster parents. The inmates of workhouses were a very mixed community; men and women, young and old, from tiny babies born there, to the totally senile. Some were there for days, itinerants passing through the town, others for years on end. Some were purely work shy, some genuinely out of work, some chronically sick. The Kettering Admissions book discloses some very sad and disturbing cases of families deserted by fathers, and sometimes mothers too. Occasionally both parents had died and there was no surviving relative who would care for the children; true orphans. The At the fortnightly Kettering Guardians’ meeting held on In other parts of At the meeting on Plan from abstract of title 1897:

The building at the corner (“from Finedon Station” at bottom of plan) was the then recently built Church Mission Room; now a private house. The small building at the lower end of the triangle survives. It was the coach-house and is now a garage. The narrow jitty still separates it from the row of early stone houses, marked “J.C.Eady” the then owner, now 1, 3, 5, See present day picture of these buildings below.

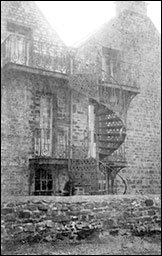

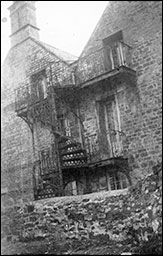

The most significant changes made to the house at this time were the provision of a fire escape and the creation of a bathroom. The fire escape was sited on the north side of the house and served the two upper floors. Each floor had a balcony serving two windows, and the balconies a common spiral staircase to the ground. The four original Georgian sash windows were replaced with pairs of French window doors to allow easy escape. Some of the changes to the stonework and mismatching of lintels can be still seen. The heavy cast iron staircase was purchased from Walter MacFarlane & Co. of the Saracen Foundry, Glasgow, and installed in April 1897. It remained in situ until 1950 when concerns about its maintenance and possible domestic burglary necessitated its removal. The present small balconies on the north side now have railings with scroll shaped cast iron balusters originally on the staircase. These pictures show the appearance shortly before removal of the fire escape.

Present view. Note surviving lintel of vanished Georgian window on right hand first floor:

All photos courtesy of John Peck The bathroom was also created in April 1897. It is unlikely that it replaced an earlier one because previously the house was not on mains water, indeed shortage of water was complained of several times at meetings as if the well had run dry. Mains water and sewage were not installed until April 1908. The first floor bathroom was constructed of yellow bricks and sited over the existing back doorways. Similar brickwork was placed round those doorways and the kitchen windows. Some sash windows were renewed. In the summer of 1897 staff were appointed. From the thirty applicants Mr. & Mrs. John Browning as Superintendent and Foster Mother, and Miss Marie Proofe as Assistant Foster Mother were appointed. They were to start work on 1st October 1897.

In September of that year tenders were invited for the furnishings and equipment of the Home: The extensive list includes 39 wire spring mattress beds complete with hair mattresses, each with under blanket and three top blankets. Sheeting, waterproof sheeting and red and white counterpanes are listed, - together with 3 dozen “enameled chambers”, also cutlery and ¾ pint mugs. These together with numerous other items were all new supplies. Any modern thought that the children may have had only worn out cast off furnishings is entirely wrong. Similarly tenders were placed by local tradesmen for supplies of food and coal. Arrangements were made for the engagement of a Medical Officer: Dr. H. Burland of Finedon was appointed. He and his successors made regular visits to examine the children and were required to make full reports at the Guardians’ meetings. All children were to be vaccinated against small pox. On At last, it is

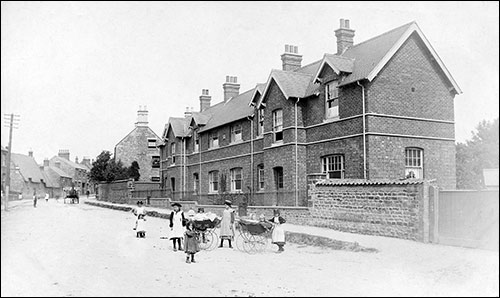

For a fuller list of children at the Cottage Homes, click here They were in a big house, with a big garden. The regular daily routine included keeping their rooms clean, regular feeding, and school. The older boys working the garden, the older girls learning sewing and simple domestic tasks, ensured they were all well occupied when not in school. The fruit and vegetables grown here and on the additional acre of ground in Finedon road supplemented their diet and helped supply the Workhouse in Within three weeks of opening, Mr. Browning, the Superintendent, had asked of the Guardians about the children receiving family visits. This was immediately granted for Saturday afternoons, A Ladies Committee was formed of seven Burton Latimer ladies whose responsibilities were to make unannounced visits to the Cottage Homes, which they did, reporting back to the Guardians’ Committee on a regular basis. The Superintendent was also required to be present at the fortnightly meetings and make a report. Christmas 1897 became the first opportunity for the Ladies Committee to show their generosity to the children. The Minutes record thanks to them for gifts of “sweets and books” and that Lady Hood of Barton Seagrave Hall had provided Xmas trees “including one for the children at the Cottage Homes”. Another had given money to each child, and all the children had attended a “tea and entertainment” with the Burton Latimer schools. In subsequent years it became the established custom that at the last Guardians’ meeting before Christmas a collection was made with which to buy toys for the children. Some of the lady Guardians became most determined: By March 1898 it was clear that whilst the system was working that major improvements were needed to improve conditions for both children and staff. Firstly it was necessary to accommodate many more children. Secondly it was impossible in the single building to isolate a child with any sort of contagious illness. The Medical Officer, Dr Burland, had reported that an isolation ward was needed. The Board discussed these problems repeatedly over the next eighteen months. The Cottage Homes had been bought with a loan from the Prudential Assurance Co, repayable with interest over thirty years. Whilst they owned the property the additional cost of more accommodation and a separate isolation ward, all entirely new buildings, at estimated costs greater than hitherto expended, required much care. The operations of local Boards of Guardians were funded by a proportion of local domestic rates, and then, as now, councillors and Guardians were under great pressure to keep taxes minimal. On Late in 1900 work commenced building the “New Cottage Homes”, now 163 and The New Cottage Homes were constructed as a semi detached pair of houses. They still retain the original brickwork and Rosemary roof tiles though some windows have been modernized. The isolation ward now has modern concrete tiles and the brickwork rendered. Initially only one of the New Homes was used, probably 163 as being the nearest to the old building. Surprisingly it was 1915 before an internal doorway was made to connect the two new houses. Each had a bedroom for an “Assistant Foster Mother”. The Matron/Foster Mother, Mrs. Browning had her own accommodation with her husband, the Superintendent in the old house, wherein there had always been an assistant foster mother’s room. It is not possible to definitely identify which rooms were which, though most of the rooms used as dormitories can be identified. The Board Minutes record that some children were to be sent from the Workhouse to the Homes on

During the following year, 1902, there was a much greater intake. At any time there would be 40 to 45 long established children, many here for a number of years, and truly living in their only home. In addition, reflecting the ongoing character of the Workhouse, a constant flow in and out of children whose background was completely unsettled, usually because of parental inability to cope with life and care for the family. The Admissions records show many sad cases where children had to be temporarily sent to the Cottage Homes, sometimes only for a day or two whilst the parents’ difficulties were addressed by the Guardians. Ironically, true orphans faced no such uncertainties. In some cases they were legally adopted by the Board until aged 18. Some years later, on “We found 59 children, 33 boys and 26 girls. Of the boys 19 were over, and 14 under 8 years of age. Of the girls, 14 over and 12 under that age. There were 3 boys and 1 girl aged 14 and upwards. Of the boys 6 are mentally and physically weak, of the girls 7 must be so classed. The children rise at 6.00 in the summer and 6.30 in the winter. The older children help the others to dress and then stay upstairs to put the bedrooms straight, each child having a separate bed. They are down by 7.00 in summer and a little later in winter, and help in setting breakfast which is at All the children attend the Elementary schools and for this purpose leave the House at 8.45 returning at about 12.30, leave for school at 1.15, returning from 4.00 to 4.30. Play till 5.15 and help for tea at 5.30. . . . . . etc. . . “ The comment that each child had a separate bed seems strange nowadays, but Victorian census records showing large numbers of children in small houses must indicate considerable bed sharing and room sharing by siblings. To be in a Home where sleeping segregation was the norm and you always had your very own bed, was something few large families of the day achieved. The children actually attended both the Council school (now St Mary’s C of E) on the High Street, and the Church Schools (now private houses) in Church Street, according to their denomination, the majority to the latter. The daily disciplined routine seems to have had good results in that the attendance records of the Cottage Homes children were much better than those from local families. The Guardians had a dispute with the County Education Committee which in 1912 wanted to keep a separate return of “the number of pauper children in regular attendance”. The Guardians fiercely responded “their children ought to be under no conditions calculated to distinguish them in any way from other school children”. This protective attitude mirrors that of the Cottage Homes Committee which back in 1901 had requested the Ladies to “consider the question of the girls’ dress which was said to be too distinctive”. As the children grew up their adult prospects and careers had to be considered. Many of the boys expressed specific wishes. Some went to local farms at 14, “in service”, or were fortunate to get apprenticeships with local engineers, carpenters and builders. Many more were sent to the training ship “Exmouth” which accepted boys from aged 12, and where they remained perhaps 3 or 4 years. The ship was moored at Grays, On the Exmouth the boys were taught the elements of seamanship, gunnery, signaling, and how to care for their own clothes. There was great emphasis on physical training. The Captain Superintendent would write to the Board of Guardians with reports of how their young charges were doing, well or badly. At the end of their training some went into the Royal Navy as “blue jackets” and some into the Merchant Navy. In some cases the Board’s Minutes show which ship they were sent to. The cost of each boy thus trained was paid by the Guardians and was significantly more than if they had been kept locally in For the girls the opportunities were more limited. At age 14 some opted to take work in the local shoe and clothing factories, but the majority went into domestic service, usually locally. The work of course entailed basic housekeeping and cleaning, and needlework. Like the boys, it enabled them eventually to earn their own living and take responsibility for their own lives. Whilst clearly the children did not have the benefits of living with their own parents, many local organizations over the years offered support in the form of entertainment and outings. Notable amongst these was the Britannia Club who put on concerts by their prize winning band in the grounds of the Homes, and invited the children to their annual teas. Similarly, the children attended church teas and events, performed in concerts and went on outings. When the Burton Latimer Boy Scouts troop started about 1921, several Cottage Homes boys joined and it is recorded that the Cottage Homes Committee of the Guardians bought them their uniforms. In July 1922 it was recorded that four boys went to camp with the Burton Latimer scouts, the cost being raised by subscription from the Guardians themselves, - not from the Union’s funds. In 1912, the Ladies of the Cottage Homes Committee were greatly concerned at the adequacy of the training the girls were receiving and said: “They are sent out to service on leaving school with little or no knowledge of domestic work, sewing or washing, -- this is not fair to the girls or their mistresses”. The Matron at the time, Mrs. Browning, was replaced in 1913 by a new Superintendent with wife who was required to be “thoroughly domesticated, with good knowledge of needlework, washing and cooking”. There were 102 applicants for the position! From August 1914 with the advent of war, many changes took place. Whilst military service was then voluntary, a number of the Not surprisingly there were cases of able bodied inmates who refused to maintain their families being issued with military call up papers. In one case the father was prosecuted for neglect of his family, sentenced to one month’s hard labour and “to be handed over to the military authorities on completion of his sentence”. In April 1916 the Master reported he had only 66 male inmates, (less than half prewar numbers), and it was impossible to fulfill all the firewood orders. Prices of all goods were rising, or becoming unobtainable. There was frequent shortage of coal. Sometimes local traders would not tender for supplies of bread, milk or clothing for the Workhouse or Cottage Homes. If the numbers of inmates were falling, then also were the staff numbers. It was becoming increasingly difficult to fill vacancies both of foster mothers in the Cottage Homes and nurses in the Workhouse in In September 1918 the Matron of the Cottage Homes, Mrs. Foster, wrote to the Guardians requesting that a 16 year girl previously in the Homes and presently boarded out be appointed assistant foster mother. In the event she was not appointed, but there had been no applicants to fill advertised vacancies, so Mrs. Foster was at least trying to fill a gap with someone she knew. Even with the ending of the war in November 1918 there were long delays in releasing servicemen. The Superintendent, Mr. Foster, only returned in March the following year. By July the Workhouse was advertising for nurses with no experience, and appointing the only four applicants. The only applicant for assistant foster mother in the Homes changed her mind. Mr. and Mrs. Foster resigned. It was perhaps fortunate that the number of children in the care of the Union had fallen, partly because of the deaths of so many young men in the war, and partly because of the stern attitude of the authorities towards irresponsible fathers who were likely to rounded up and sent to the front. It is also likely that the Cottage Homes system had begun to break the cycle of poverty whereby children of workhouse inmates became inmates themselves, even over several generations, as the children were given regular education and training. The Guardians resolved these many difficulties by appointing a new Matron and two new assistant foster mothers. The new Matron, Miss A. Willett(s), in fact stayed loyally at her post for 4 years. The biggest change however was to recognize that to operate large houses capable of housing 64 or more children was no longer financially viable with numbers less than half that. In June 1919 the Guardians proposed that the New Homes alone be used and the Old House, hitherto the boys’ quarters, be let. In the following months the New Homes were reorganized and redecorated to accommodate all the children and all the staff therein. By November 1919 the changes were completed and Mr. A.J. Sturgess, the Relieving Officer for Burton Latimer had moved into the Old House. In May 1920 even the Isolation Ward was to be let, this to Mr. S.Gillard, the assistant clerk to the Guardians. To date (2006) we have not found the precise numbers of children in the Cottage Homes at this time, but the meeting of By September 1922 the Guardians, noting that there were now only 13 children in the Homes and expecting further reduction, voted to board out those suitable, and ultimately to dispose of the Cottage Homes. Future children to be boarded out in certified private homes, the staff to be offered compensatory payments or employment at the Workhouse. The Ladies Committee formed an after care committee to oversee children placed in homes or other institutions, each looking after one or more by visiting. On It only remained for Miss Willetts to complete the inventory of furniture and equipment and prepare the premises for auction. On

“3” is the original, Old House. Bought by the Buckby family. “2” the Isolation Ward “1” the New Homes. Some time after the auction, the New Homes and the Isolation Ward were bought by Mr. Frederick Turner, who owned a china business. He later built a warehouse and shop on the north side of “1”. This is now 161, High Street, the Nursery School. The years had moved on, and no doubt the Guardians felt their decision correct, but of course the problem of how best to accommodate needy children had not gone away. In January 1926 the Committee reported they now had no separate accommodation for children over 3 years old; those under that age could be kept as always previously, in the Workhouse nursery. They now had eight children in need of homing who were not suitable for boarding out or fostering. Some were sent to the Leicester Cottage Homes at Countesthorpe and others to the Waifs & Strays Home. By summer 1926 the Committee made serious enquiries as to renting Ferndale Lodge, on Headlands, Government attitudes towards the administration of Poor Law and Relief had been changing since the war and the effects of the depression. The Local Government Act of 1929 proposed that all Poor Law functions be transferred from the locally elected Guardians to County Councils. Whilst some Unions requested delay in enactment, Guardians, all living locally and elected, particularly the Cottage Homes Committee, knew individual local children and their families, their history, their problems, and their districts extremely well. It is very unlikely that serious cases of cruelty or neglect would have taken place without their early knowledge and remedial action. Some served for as long as thirty years, entirely voluntarily, at all times subject to the ongoing approval of the local ratepayers. The Unions of Guardians served their communities well for almost a hundred years. It is highly debatable whether the changes made in 1929 were an improvement. Click here to read Ernest Dainty's account of life at the Cottage Homes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||