| Written by Stan Simons 1999, reproduced by kind permission of his daughter Diana Glasspool. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

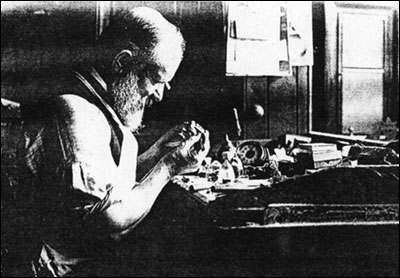

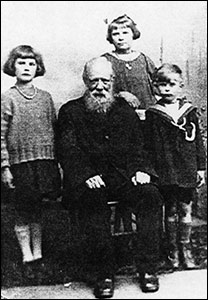

Born on the same day that General Sir Stanley Maude and his troops took My story begins in Derbyshire, at the ancestral home of the Duke and Duchess of At that time the 6th Duke only employed, as his personal servants, people who were large. The coach my ancestor drove is still on display at Chatsworth. My mother was born in 1886 and named Ellen Stevenson but she didn't like this name and always referred to herself as 'Helen Stevenson'. This is the Christian name on both her marriage and death certificates. She had a younger brother, Charlie, and an older sister, Annie. The family came from Uncle Charlie went to work in the mine at the age of 13. Whilst there he got friendly with an Irishman known as Paddy who one day said "I'm leaving to go to My Mum said if Paddy had sent money Charlie would have spent it. As it was he set off for the six weeks journey with very little money in his pocket, most of which he had spent on the voyage. Just 15 years of age he landed in At the outbreak of World War One in 1914, Paddy said he was going to join the Army and my Uncle said in that case so was he. On the field of battle the Australians were retreating and my Uncle was shot in his left eye, the bullet going right through his head. As he lay seriously wounded two Germans appeared and Charlie tried to get out his revolver, seeing with his good eye, which obviously was impossible. The Germans went away but came back with a wattle on which they placed my Uncle and then carried him to the Australian lines. They shouted: "Wasser, Wasser," to which the Aussies shouted: "We'll give you wasser you b — s." The Germans then said, "No comrade, Wasser" [meaning water]. At this the Germans were welcomed with opened arms and given food and cigarettes. I believe they were fed up with the war and wanted to be taken prisoners. At the casualty clearing station he was left among the dead and dying until a medical officer came by and Charlie, looking out of his good eye, asked for a cigarette. The Officer said that if he were well enough to smoke a cigarette then he would see what he could do for him. This undoubtedly saved his life. Taken back to Mum's sister, Aunt Annie, married a William Smith and they also emigrated to Mum's father came to My Dad was born in Sibbertoft, near Market Harborough. His father died at the age of 24 from diabetes, but his mother married again to a Mr. Warren, who was a clock repairer. I have a large prize winning photograph of him, at his bench, with an eyepiece, mending a watch. They lived at

Step-Grandfather Henry Warren was a very active man and was happiest when using his energies and effort in some sort of work or organisation. For many years he trained and conducted a choir of young people in the town, who annually visited the

Mr Warren was very devoted to the One morning, at the age of eighty, he went down to the docks to visit his old friends, when he fell into the water, just as the ship was a few feet from the harbour wall. The time was 11.10 a.m. and my Aunt Nellie was in the garden, hanging out some washing, when she ran into the house distraught and cried to Uncle Charlie: "I've just heard Grandad calling Nellie, Nellie." He said, "Don't be daft," or words to that effect, "he's down at the harbour," some nine miles from where they lived. They looked at the time and it was 11.10 am. Grandad My father tried to join the Army at the beginning of the First World War but was rejected, as he was said to have a heart condition. He then lived to be 92 years old, and when he died this was nothing to do with his heart. His great love of life was music, and he played the trombone in the Wellingborough Silver Band before the First World War. After the War he played for many years with the Kettering Rifle Club Band. He was also a gifted baritone singer and sang at many an Eisteddfod in When he eventually lost all his natural teeth he had to give up the trombone. Mum had a friend in Dad worked as a foreman packer at the Holyoak Boot and Shoe Company, Kettering, owned by the Co-operative Wholesale Society and was Secretary of their Welfare Fund for many years. He was responsible in purchasing many books to be presented to scholars at the various schools in the town. I recall that I won one and my sister Madge another. Often the house was filled with lovely books. I'm afraid that I was a disappointment to Dad. Although I took piano lessons for five years, tried the trumpet and the violin, I was no good at any of them. I do however appreciate good music, especially the songs my Dad used to sing. |

||||||

|

||||||