1914 was the year I was born [as William Charles Fuller], July31 to be exact. What a time it was to come into the world, just before the First World War. Already my father Arthur Fuller and mother Annie, God Bless Her Soul, had had my sister Lily four years my senior, and soon to come was my brother Horace born eleven months before myself on July 1st 1915.

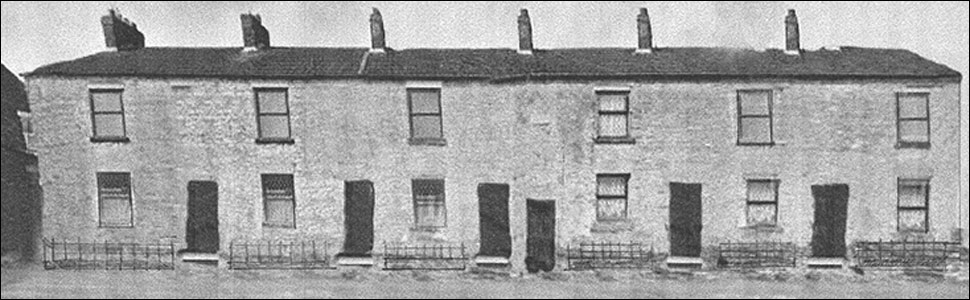

We lived in a small terraced cottage in Caroline Terrace, Finedon Road, Burton Latimer, two up and two down, no kitchen, water from a stand-pipe in the yard, toilets in a row away from the house. Each house had a barrel to catch the rainwater for washing. The bath was made of tin, about five feet long, and when not in use hung from a large nail outside the back door. Toilet paper? – never heard of it – the News of the World, cut into regulations squares, secured to the toilet door with a shoe lace, having a made a hole in the corner by an awl as used in the shoe trade. None of the ‘fancy stuff’ in those days, piles? – never heard of them.

At the age of three I attended the Mission Room infants’ school. Which was more or less over the road from where we lived. Miss Lewis was one of the teachers I remember, she taught us our tables and we respected her.

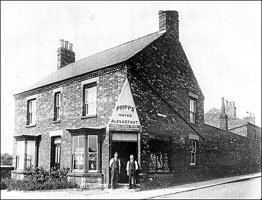

From this tender age I was sent on errands to the corner shop nearby. The shop was owned by Mrs. Liz. Allen, a rather tight-fisted woman. I can remember Mother sending me with a cup to buy a penn’orth of treacle to put on a suet roll. Mrs. Allen would first weigh the cup, then dip a large spoon into a big stone jar and put a penn’orth of treacle into the cup and not a drop more. She would then lick the spoon before putting it back into her jar. On occasions I was sent to buy pickled onions, these were also weighed and if the scales went down with a bump Mrs. Allen would bite one of the large ones in half.

|

|

|

The Mission Room Infants School, Finedon Road

|

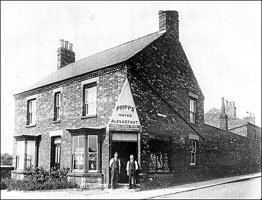

Allen's corner shop in later years

|

The treacle had other uses, which I well remember. Every Saturday evening, we were given a concoction to clear the blood of all impurities known to man at that time. The ingredients did vary, but usually consisted of liquorish powder mixed with treacle. It worked wonders, a spoonful and you nearly went into orbit! On Monday there would be delayed action, much to Miss Lewis, our teacher’s, dismay, the pong being horrible. She would frequently ask, “Does anyone want to go the toilet?” No one would say yes for the shame of it. By the next Friday you could say it was clear in more ways than one, ready for the next dose on Saturday.

The war ran from 1914 to 1918, during this time Mother had us three small children. Being the worse for wear after a heavy bout of drinking, my Father, with a few of his cronies, walked to Kettering and joined the army, leaving Mother to fend for us. We had nothing, so she had to go to work in the shoe trade at Fox’s, the boot heel makers. Us three children were looked after by anyone who would have us while she worked. A Mr. and Mrs. Reynolds were very kind to us. Mr. Reynolds was the local road sweeper – brush, shovel and cart in those days.

During 1917-1918, food was in very short supply, only regular customers were being served in the shops. Lack of food caused me to have malnutrition, big belly and knobbly knees. The local doctor sent me to the Clinic in Lower Street, Kettering, for medication, which could be obtained there. On examination it was confirmed that I had rickets and was prescribed a large jar of cod-liver oil and malt.

It was during this time that brother Horace gave Mother a real scare; he was coming down the stairs crying his eyes out, hardly able to walk. Mother sat him on her knee, very concerned of course, on careful examination he was found to have two legs down one trouser leg. Of course, this was soon put right with a few choice words from Mother.

The Great War ended in 1918, with Father returning without a scratch. Due to the fact that he had very bad bunions he had served as an Officer’s Batman throughout the war. If there had been a prize for the biggest bunions I’m sure he would have won it. As young as I was then, I could sense that all was not well on the home front. Mother, bless her, was very short of money, the main reason being that Father drank like a fish, it was said he had shares in the brewery. My memory is clear to this day, Mother asking “Where’s the housekeeping money?” It had all gone on booze. In her anger, Mother said to him “I was managing better without you, it’s a pity you came back.”

Soon after the war ended, I was about seven, we left Caroline Terrace for Spencer Street. This came about as Mother was expecting Phyllis. Horace and myself were sent to an Aunt and Uncle at Broughton for the weekend; they had a shop in the front room, selling sweets and ice cream. This was a treat for lads like us, having been restricted from sweets through lack of cash. When we got home, there was the baby in its pram-cum-cot. Asking where it came from, we were told under the gooseberry bush, even in those days it did sound odd, to say the least.

Money for Mother was always a problem, not only did she wash for the family, to make ends meet she took in other people’s washing. She was a real worker. Father was worse than useless, he couldn’t knock a nail in. The only tool he had was a hatchet, which he used to chop the wood, a hammer, and wire cutter. Friday was boot-repairing day; I had to go next door to Mrs. Turner and borrow the hobbing foot used for shoe repairs. Whilst Mother was setting the sack in the sink for the hobbing foot Father, so called, would be putting on his muffler to go out drinking, spending the money which was needed at home. I did learn, years later, he was spending as much on booze as he was giving Mother to pay the rent and feed the family. Even his own Father, my Grandfather, told me he had the opportunity to make good, but he preferred to drink.

We now had another brother, Raymond, and it became the duty of Horace and myself to take the younger ones down the road in the pram, we were nursemaids so to speak. Our weekends and holidays were taken up with this chore. Soon we were to have another brother, Sidney, almost ten years younger than myself. Dr. Warner attended his birth and the bill was for 12/-, to be paid weekly at 1/- (5p) a week. It was my job to take the money each Friday, after Father got paid, to his surgery. When 11/- had been paid, the doctor said “Tell your Mother she need not pay anymore.” For those days it was a very generous gesture, those with money didn’t like to part with it and kept it in the family.

|

|

|

Dr. Edwin Warner

Dr. Warner was Canadian

|

The Co-op stores in Duke Street.

The butchery was at the back

|

Sid was a pain in the backside. We used to take him down the road and sit on the form. No sooner had we settled down for a rest than Sid would perform his party piece, for he had trouble with his bowels. We would quickly push him home smelling of sweet violets to be met with Mother with a few choice words and a bucket at the ready. The pram was turned on its side and swilled with water, and Sid duly cleansed. (To this day, Sid has stomach trouble.)

Another duty given to Horace and myself was to go on errands. We took it in turns, one week to go to the Co-op Butchers managed by Fred Dunmore, the following week we were delegated jobs or errands by our Mother. Both of us hated going to the butchers to ask for four pennyworth of shin of beef, penn’orth of suet, penn’orth of liver to be wrapped in the News of the World – none of your fancy wrapping of today, a bit of printer’s ink did no harm. On receiving the meat, which was to feed eight, Mother would unwrap it and see if it was up to standard. “You can take that back, it’s all fat and gristle, and you can tell that Fred Dunmore that Mother said you palm us kids off with anything.” Mother’s word being law in the household, we soon got moving in no time back to the butchers. He knew what was coming and would bang the ‘big’ order of meat on the chopping block, using a few choice words, unwrap the meat from the News of the World, which by now was sticking to it, and exchange it. On arrival home, Mother would duly examine the new lot, and nod with approval. “That’s better, now hurry or you’ll be late for school.” Horace, being a proud lad, once said “I’m not taking it bac.” “WHAT”, Mother said, and chased him up the street with the copper stick (technical word for the leg off an old wooden chair.)

As you can see, we were poor, same jumble sale clothes every day of the week; Father drinking the money and buying clothes for himself. Boots, a shilling a week from Coles’, Newman Street. Mother, as I said before, did our shoe mending using an old rubber tyre, which did 50 miles before re-tread.

The boot and shoe trade from Christmas to Easter was a dead loss, not knowing who would be ‘getting their cards’ next. When Father was in work, it was usual on a Friday, which was pay day, for him to have a tupenny-halfpenny tin of sardines for his tea. It was my job to go to Payne’s corner shop just over the road to fetch these. On one occasion, just after Christmas, Father came home from work with his little box, which held his clicking knives, for he was a clicker cutting out leather for the boot tops. This was at five o’clock. Mother, seeing him with the tools of his trade, pushed me out the front door with the tin of sardines, shouting that I must take the sardines back to Payne’s and get the tuppence halfpenny back, and tell them “Father’s out of work and Mother can’t afford them.”

|

|

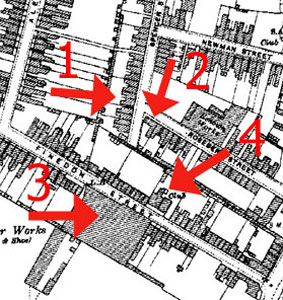

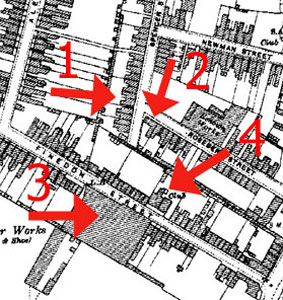

1: The Fuller home,11 Spencer Street

2: Payne's corner shop

3: Finedon St. W.M.C. (The Rack)

4: Whitney & Westley's factory

|

Father, as you will have guessed by now, was a heavy drinker, his preference being strong ale. After work on Saturdays, it was the practise among the dedicated boozers to go to the ‘Rack’ Club opposite the factory where they worked. Mother, on one occasion, being short of cash, the stuff that paid for the rent and food, picked Sidney up in her arms and went down to the ‘Rack’ where she knew Father would be. She plonked Sidney on his knee, and in no uncertain terms told him “Here’s your baby, now look after it.” As in those days flat caps were the fashion, all the men looked similar and Mother had plonked the baby, not on Father’s lap, but on that of some poor unexpecting soul, much to the amusement of everyone present.

As a child, Christmas wasn’t a very cheerful time. Once, when Father was ‘on the dole,’ the neighbours rallied round and gave Mother a shoe box full of groceries, which saved the day. Often all we had in the house to eat was a bit of bread and dripping. Mother would sometimes go without her own dinner so us kids could have a bite, saying she wasn’t hungry. Our next-door neighbours Mr. and Mrs. Turner sometimes gave us ‘pig’ potatoes, the small ones, which Mother would boil up in their skins. Talk about living it up! Dipped in a saucer of salt, it was nectar to us. During the winter months if we had, or were given, some stale bread, Mother would make us kettle broth. WHAT? Never heard of it? The kettle was heated on the fire, and Mother would cut the bread into squares and then pour the hot water over it, if there should be a copper to spare we might have an Oxo mixed with the water between us. Never had it so good! Then off to bed with a full belly.

The winters were very cold, with frost on the inside of the bedroom windows; we only had one fire in the house – in the living room. For fuel we had leather bits (off-cuts of leather from the shoe factory) mixed with gas coke. The coke was fetched from the gas house, usually on Saturday as father had just been paid. We used the pram to carry the coke; it cost us sixpence a big sack. One particular man would always give us a couple of extra shovels-full loose in the pram. Mother didn’t seem to mind. On one occasion, Lily and myself got caught in a blizzard going on the coke run, we were frozen and unable to push the pram because of the snow. After some time, Father appeared, not in the best of moods for he must have lost his afternoon nap after his ale session.

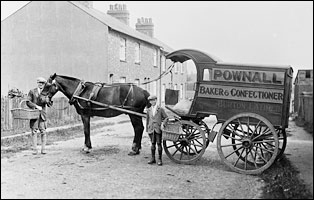

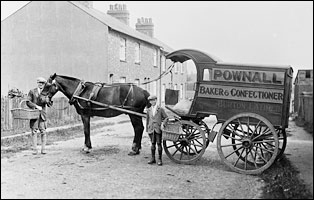

Of course, time was moving on, and at the age of twelve Mother got me a Saturday job as a Baker’s Boy with Mr. Pownall J.P., with his assistant Gerald Farrow. Gerald was very kind, sharing his mid-morning snack with me. I was paid 2/6 a week and worked from 7am to 5pm. This included a dinner of corned beef, piccalilli and boiled potatoes, which we ate in the bakehouse sitting on a bench. The sweet was often damsons with custard; after we had eaten it we would count the stones round the dish to see who had been given the most.

Mother was rather pleased to receive two shillings of my wages and I kept sixpence – lucky me! After tea on Saturday, Ray and Sid would pester me to send them over to Payne’s shop to buy six halfpenny lucky bags, which contained sweets. It was then my job to tip them on to the table and share them out. Horace was not involved in this orgy as he preferred to have his own sweets, which he ate reading the News of the World, hoping no one would notice – a very odd carry on.

|

|

|

Tim (centre) with Gerald Farrow in Bird Street

|

Tom Miller's paper shop, High Street

|

Mother had heard ‘on the grapevine’ that Mr. Miller the newsagent was looking for a lad to deliver Sunday morning papers. Who else but the bright lad, me. Horace couldn’t do it for he liked to stay in bed on a Sunday morning. The wage again was two and six, two shillings for Mother and sixpence for me. I could put sixpence away for a bike from Charlie Ward’s, which cost ten shillings cash, second-hand. With the extra money I was able to give to Mother, she was able to buy some of the better clothes at the jumble sale, she no longer had to wait for the throw-outs at the end – happy days! We could even afford a joint of beef on Sunday. Mother often used to walk to Kettering Market after tea on Saturdays to pick up a bargain piece of meat. Topside was her favourite joint: hot on Sunday, cold on Monday with jacket potatoes (Monday was the big wash day), minced on Tuesday, Oxo stew on Wednesday. What was left of the meat, Mother cut into small pieces and it was a bit of a lucky dip as to if you found any meat.

Mr. Turner, our next-door neighbour, would go out shooting rabbits and any surplus to his family’s requirements he would sell for sixpence each. If Mother bought one we had a real banquet. Mother would skin and clean the rabbit and cut it into small pieces so we could all have a share. Father was useless, he had no idea how to cut a joint or even a loaf of bread. The only place he excelled at was at the bar of the ‘Rack.’ Between the ages of twelve and fourteen, I was ‘in the money,’ shilling a week and doing quite well at school. Mr. Davies, one of our teachers, knew of our circumstances as he collected our rent, the house belonging to a friend of his. At fourteen we all sat exams at school; this was rather pointless as only the better off could afford to let their children go to the grammar school, most would be unable to afford the uniform, no matter what the result. So, at the age of fourteen and proud owner of a bike, Mother took me to Timpson, Bullock and Barber, Engineers, Bath Road, Kettering, for a job. One of the workmen must have known I came from Burton Latimer and said, as a lathe turner, his wage was lower than in the shoe trade. My wage was then eight shillings and I could have earned nine in the shoe trade. Luckily, I had to take a shoe machine part from T.B.B. to Buckby Brothers, Burton Latimer and I asked to see the foreman of the lasting room, Mr. Shatford. This was mid-week and he said I could start the following Monday at nine shillings a week. Just a few coppers extra for Mother, Phyllis, Ray and Sid to enjoy the fruits of my labour, and I was proud to help.

|

|

The lasting room at Buckby Brothers at the time that Tim worked there. Could he be in this photograph?

|

Mother was still repairing the shoes to the best of her ability, but I thought I might be able to help in that direction. I approached Mr. Chambers, an elderly man who had made shoes in the past and asked him if he could please help me to have a go at the repairing, as Mother was doing at the moment. With tears in his eyes, he said that I could go to his house after tea and he would start me off. I duly went to his house and he gave me two iron shoe lasts and an upright stand, asking if I had a hammer and nail puller. I told him the only so-called tool I had was a hatchet. So I set off home with the tools of the trade so that I could repair the family’s boots to the best of my ability. Scrap leather, rubber and nails I ‘borrowed’ from Buckby’s – they didn’t miss the pickings off the floor, they would only be swept up and thrown away. Mother was pleased I had taken this job off her hands.

You are entitled to certain perks when in full-time work, one being fish for tea on Monday, perhaps a kipper or bloater. Sid and Ray would breathe down my neck whilst I ate my fish. They would take it in turns, one to have the skin and the other the bones, which I would leave some fish on. The bone boy didn’t hesitate to crunch the bones up. Little did I think to share it with them?

During the winter months Buckby Bros. would be on short time. The orders slow to come in, the football and cricket shoes only being made to order in those days. Mr. Wilson, who lived in Little Harrowden worked on the bench, and if we had a half-day he would borrow my bike to go home. After dinner I would walk to Little Harrowden to get the bike back. Mr. and Mrs. Wilson had no children and they made a real fuss of me, something I had never known before in my life. I would go with Mr. Wilson to the allotment to dig the ground and get carrots, beetroot, cabbage – whatever was in season. On returning to the house at teatime, tea would be ready EGG, BACON and FRIED POTATO, a meal fit for a King, not what a half-starved lad was used to. Mrs. Wilson would send me home with a few eggs for Mother if she had some to spare. Mr. and Mrs. Wilson wanted to adopt me. I asked Mother but she said no. What might have been my lot if she had said yeas, who knows? At Buckby Bros., if someone left or was put on the dole, the foreman would ask if you would like to operate the empty machine. I soon picked up most of the jobs, which stood me in good stead in future years.

At nineteen, I started to look for a new job, we were often on short time and I wanted to save some money. Sometimes I didn’t earn enough to pay my board and would have to owe Mother a shilling or two. So off I went on my trusty steed to Kettering, Rushden, Irthlingborough and Wellingborough, where I managed to get a job at Gilbert Bros., Park Street. I biked every day to work and instead of being on short time it was overtime and at the end of the week I had money left.

This gave me the incentive to save as, from the age of seventeen, I had begun courting Margaret Sharman, of Glendon Lodge, Burton Latimer. Margaret later became my wife, as by the time I was 23 and Marge 24, we had saved enough money to get married. We rented two rooms in a house, which we furnished ourselves. On April 18th 1938 we were married at All Saints Church in Wellingborough. The reception was held at the Granville Hotel, the menu, ham salad, trifle, cakes and tea at ONE and ELEVEN a head. I must point out that before the war the total cost for fish and chips was threepence – one penny for chips and two for fish.

|

|

|

Tim Fuller in his twenties

|

Margaret Fuller nee Sharman

|

In July 1937, the year before I got married, we came in for quite a shock. I had just returned home from courting to be met at the door at 9.30 by a certain member of the family just going out. “Tell Mother I’m getting married in the morning.” “You’d better come with me and sort it out yourself.” I said. Of course Mother went spare asking why she hadn’t been told before as she could have helped. Yours truly agreed to be Best Man. The wedding took place at Wellingborough Register Office. After the ceremony, the Registrar asked the Groom for seven shillings and eight pence. The Groom made no effort to pay, so I coughed up. When we got outside I asked the Groom if he had any money. He hadn’t, but replied that he’d paid for the rent and had the groceries for the next week. I felt in my pocket and gave him two pounds to help him out of the situation. It was a sad day for the family.

As I said before, Christmas wasn’t goodwill to all men. One July, when I was about fifteen and working at Buckby Bros., already realising there would be little to eat at Christmas, I purchased a Christmas draw ticket from Kettering Thursday Football Club for a penny, which I placed in my waistcoat pocket. The winner was to be announced in the Evening Telegraph before Christmas, the first prize a turkey. We didn’t take the E.T. but our neighbour Mrs. Bull did, so I asked to look at her paper. Much to my amazement my one-penny ticket had won first prize. I kept checking the number, 1399, again and again. I had to go to the secretary of the football team in Rockingham Road, Kettering to claim the aforesaid turkey. Being at work and earning a few shillings for Mother and myself, I paid the bus fare to Kettering out of my own pocket, sixpence return, and I proceeded to the secretary’s house. He gave me a voucher for the turkey and I had to walk to the High Street butcher’s shop. On giving him the voucher for the turkey the misery said “Another win for an outsider!” Anyhow, I took the LARGE unwrapped turkey back home on the bus. What a picture to see Mother’s face, she was over the moon, she didn’t kiss me, it was not the fashion in those days. Being a good cook, she cooked the turkey to perfection for our Christmas dinner, it lasted for best part of the week.

By the way, some months earlier whist working at Timpson, Bullock and Barber, I had a penny ticket for a draw and won a brace of pheasants. At the time I was off work ill but someone from Burton Latimer who I worked with delivered them to Mother. Mother dressed the birds, feather picking and gutting them herself and provided us with a good meal whilst father looked on. He would arrive home from the ‘Rack’, eat his meal and not give a thank you to anyone.

Then came the war. I thought it would never end. I spent five and a half years as a storekeeper, serving in England then France, Holland, Belgium, Germany and Iceland. The civilian workers here also put in a supreme effort making boots and shoes, army uniforms, including greatcoats. Men were retained to work in the steelworks, on the railways and work the farms and forestry, to mention a few of the reserved occupations. After a busy day at work came the home guard and fire watching among other tasks. Food was rationed and people living alone at home, like my dear Wife, were actually starving. A good friend with a family, with a husband working on the railway, would occasionally have a little cheese, fat or butter to spare, which they would give to her. It was usual to work from 7.30am to 8pm, sometimes six days a week to meet demands. The iron and steel furnaces operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week. My wife lived with her sister in Wellingborough for part of the war. Unfortunately, the house was hit and demolished during a bombing raid, the roof and windows being badly damaged. Marge went to live with my Mother and Father in Burton Latimer, biking to work every day until repairs were completed.

|

|

Margaret was bombed out when Wellingborough was attacked in 1942

|

Kathleen, our dear daughter, was born on February 23rd 1944 at Woodfield Nursing Home, Finedon. The war finished September 8th 1945 and I was demobbed at Cardington, complete with suit, shoes and hat, ready for civvy street. Many people wondered what the work situation would be. Would it be the same as after the First World War? Thousands of of unemployed and some soldiers re-joining the army to go to India, the Khyber Pass etc.? Gladys, Marge’s eldest sister, emigrated to Australia with what was called ‘the ten pounds assisted passage.’

Mother and Father were by themselves after the war as everyone was by now married. We had all served our country with the exception of Lily. Horace in the Signals, Ray and myself in the R.A.F., Phyllis in the A.T.S. and Sid in the Marine Commandos. Luckily, we all came back in one piece to go our various ways. As a family, we kept in touch, Ray and Sid still visit us now.

For me, it was back to work at Bignells, who were joined by Gilbert Bros. and became known as Bignells Ltd. There was plenty of work for us. A recession was to follow, but we weathered the storm. I was pretty adaptable using shoe machinery and was able to do maintenance work and, after a year or two, I was asked to become a member of staff. This meant that I would be paid even if we were on short time. During these periods I did major maintenance work fitting new bearings on the shafting, decorating, and learned to start the 110 HP gas oil engine as the old fellow who ‘ran it’ was not in the best of health. My job in the factory was as a rough rounder, which in due course resulted in a hernia. I had three at different times and, after the last one, was advised by the doctor to get another job. So after 30 years of hard graft in the shoe trade it was time to make a change.

|

|

|

Bignell's, Wellingborough

|

Wellingborough Technical College

|

The Technical College at Wellingborough advertised for a caretaker, 28 people applied for the position and I think because of my maintenance experience in the shoe trade I was offered the post. What a difference to slogging away in the shoe trade. No targets to meet, needing 70 pairs one week, 75 the next. On joining the Technical Institution, as it was then called, the classes were held in various buildings, the lower floor of a doctor’s house being the office, where three people were employed; above them in the same building was the engineering drawing office and the painting and decorating department. An old ex-army hut housed the shorthand and typing department; the welders used a lean-to shed, whilst the plumbers and carpenters had the use of a fairly new prefabricated building. The main block on Church Street contained the science room on the first floor and the radio and television classes were held in the basement. Mr. Abrahams was responsible for these. The entrance to the Church Street building had two front doors, the one on the right led into the Institute, the one on the left to the Council Chambers. The ambulance and fire brigade stations were housed in a building to the left of the Institute.

After being at the Tech for only six months, I was appointed Head Caretaker as the other two caretakers had reached pensionable age. Plans were afoot to build a new College but to do this all the old building had to be knocked down for the work to progress. In due course the new building, now called Tresham College was completed. Sir Gyles Isham opened the building, accompanied by other big council members. I knew my way all over the building, every corner so to speak. It wasn’t a warm place by any means, all glass windows, front and back, letting in a draught, no matter how the three large boilers struggled, it was hopeless.

A lift was installed for use of the teachers and students capable of carrying eight persons to the various floors. Of course, students being students, piled in causing the lift to stop before it reached floor level. This meant going to the top of the building to the lift gear motor room to hand wind them down to floor level. Not a job to be looked for. The clocks in the building, powered by electricity, were made by Gents of Leicester, the master clock was in the main office and there were slave clocks in every room, which could be regulated to the nearest second. Gents installed the clock system in the Houses of Parliament and other important buildings.

I enjoyed my stay at the College. Mr. George, the Principal, was a fair man and would always listen to complaints from both sides. Only on one occasion a teacher made a complaint about some triviality and I had to go ‘on the carpet’. The Principal, on only hearing the teacher’s side, started to chew me up. I said to him “This is the first time that you, the Principal, having heard only one side of the story, has made your decision, would you please hear me and get the so called gentleman in here so I can hear his petty complaint.” CASE DISMISSED. Of course, we had a trade union N.U.P.E. which sorted out a lot of problems for us at the College, such as not being paid for overtime, payment for hall lettings for dinner dances etc., which, as being the lowest paid workers for the County Councils, meant a lot financially to us.

During my time at the College (18 years) we moved from Mill Road to No: 58, Roberts Street, both in Wellingborough. It was hard work, the house was in very poor condition, but yours truly and my dear wife did eventually make it a good home, complete with garage and good-size garden. Kathleen and Brian, the son-in-law, helped as much as they could. When decorating, Marge and myself would spend the whole of Sunday working. To cook, we used an electric frying pan to cook a meal. The meat and vegetables were all put in the pan and cooked slowly for a couple of hours or so. We really enjoyed our meals, even in the muck. It was a three month non-stop battle to get the house ready to move into because we had already sold our house in Mill Road and the new people were pushing to move in. Kathleen and Brian at this time were living in Scott Road, they had one child, Martine, born in 1968. But they were soon to move into Roberts Street themselves, where they has another daughter, Karen, born in 1971.

There were two additional postscripts added to the account above. The first was written in about 2002 when he was a resident in Latimer Grange, Burton Latimer. The second was written in 2004 when a resident in Park House, Wellingborough.

William Charles Fuller Date of birth 31 July 1914 Margaret Alice Fuller Date of birth 6 December 1913

Latimer Grange 119 Station Road Burton Latimer NN155PA

The reason for being here at Latimer Grange is, after looking after my wife Margaret who has DEMENTIA for 10 years I had a physical and mental breakdown and was recommended after some searching, to Latimer Grange. We have now been here for 18 months, there being no change in the condition of health for my wife Margaret, but I say without fear or favour that I am enjoying myself to the best of my ability, mostly reading books non-fiction, also water colour painting which I do enjoy, of course I’m only amateur doing my best. Perhaps I’m rather lucky to be able to go for a walk with a stick around the block weather permitting. At Latimer Grange all of my personal worries are behind me, everything which is needed for our welfare is looked after by the Managers and Carers not forgetting the cooks and cleaners a wonderful lot of people, nothing too much trouble 24 hours a day. Clean beds, towels daily, the meals are of a high standard and should you fancy something different than on the menu every effort is taken to get it, given a short notice of course. The decoration at Latimer Grange is of the top Quality, the furniture akin to home easy chairs side tables foot rests if needed Carpets everywhere. The wallpaper must have cost at least 1/11 a roll in the old money (we old fogies can’t get used to the new prices.) Any furniture which we had at home and wished to bring here, coffee table, writing table etc. are most welcome, not forgetting photographs. Of course we have a cross-section of residents some are able to attend to their personal needs but on a regular basis those in need are taken to the toilet by the dedicated staff with every care and consideration, not a job everyone would want to do, more so on shift work which must need getting some use to. Amenities It is regretted that some of the residents cannot take advantage during the so called ‘Summer’ of the beautiful gardens and lawn, those on a Zimmer if they so wish are taken outside and supplied with ice cream or cold drinks which is most acceptable, also once a month we have a ‘Sing along with Jim’ for about an hour. We who are able give our tonsils a treat rather good we are, I think, should the ‘Latimer Grange Quartet’ be available it’s icing on the cake. We have had a visit to the theatre at Wellingborough but I’m sorry to say it didn’t get the support required for further outings. Visitors are welcome at most times either in the lounge or in the dining area and if there is anything personal to discuss we are escorted to our bed sitter either walking or should it be upstairs chair lift. Conclusion. Latimer Grange is for me the place to end my days. I try to make it a holiday, I’m sorry to say my dear wife does make it hard to enjoy myself fully, it’s not her fault, it’s the dreaded word DEMENTIA could be worse no doubt. We, like a good many have sold our property to be looked after in the ‘twilight years” and personally, I don’t regret it. William Fuller 88 years old.

PPS – April 20 2004 My dear wife Margaret passed away Feb 20 2003 aged 89 years. Latimer Grange was registered as a home for retired elderly people. As from last January the manager decided to have 10 people with dementia. From then I had no one I could talk to apart from the staff who had extra work looking after the ‘poor’ people and it affected me mentally. I know I could read water colour paint but I was getting ‘withdrawn.’ Kathleen (daughter) and her husband Brian could see a difference in me, so they looked for a different home. As luck would have it a room became vacant at Park House Wellingborough and I went there March 24 2004. Now I am settled in I’m rather pleased I made the move. The best thing for me is the toilet and wash basin ‘en-suite!’ Not forgetting the wonderful cheerful staff all so young nothing too much trouble for them.

William Charles (Tim) Fuller died a few months later.

|

|

|

Latimer Grange, Burton Latimer

|

Park House, Wellingborough

|

Supplementary information - Tim’s parents were Arthur Fuller, born Northampton, who died 26 Dec 1961. His mother Annie Maud Howard was born in Whitby, Yorks., but her family moved to Kettering when she was very young. Her marriage to Arthur to place in early 1910 at Kettering. She died 24 Feb 1973

Arthur was a Private in the 207th Employment Company, Labour Corps, during WW1

Tim (William Charles) Fuller was baptised at Burton Latimer St Mary’s as an adult 17 July 1932

Margaret Sharman was the daughter of William Cole Sharman and Emily Kate Annie Sharman, Glendon Lodge Farm. This isolated farm was situated between Wold Road and the A6 road to Finedon and reached by way of a track from the A6.

|

|

Glendon Lodge - Margaret's home

|

|