|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

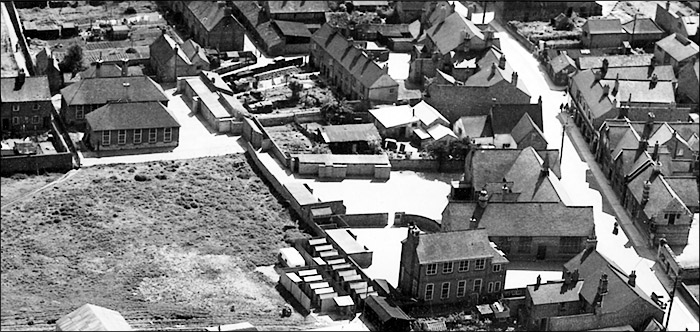

| As today, Burton had two sets of Infant and Junior Schools in the 1950s - the Church Schools in Church Street and the Council Schools in the centre of the High Street. The "Council" in question was Northants County Council, not Burton Urban District Council. Officially, the Junior School went by the name of "Burton Latimer County Primary Junior Mixed School", but everyone called it "The Council School", unless you were in the Infants School, where it was referred to as the "Big School"! All Burton schools had their intake from all across the town, there were no demarkation areas as far as geography was concerned. Denomination was another matter. If your family were Baptist, Methodist or Roman Catholic (there were no Congregational churches in Burton), then attending the Church School was out of the question.

The Council Infants School In the late 1940s the Headmistress was a Miss Capon - one of the no-nonsense school of headmistresses. She was succeeded in the very early 1950s by Mrs Williams (an internal appointment) who could be strict, but whose general manner was kinder. The reception class teacher in the early 1950s was a Miss Brawn. She was very kind and sympathetic, and very popular with her charges. There was general distress when she married and moved away.

Miss Brawn had the unenviable task of dealing with The First Day at School. This was the traumatic introduction to education. Mothers took their beloved children to school, often bearing flowers for the teacher. The mothers were then kindly but firmly instructed: "Just go". Shortly afterwards, the distressed crying and howling began, as children realised that their mothers were no longer present and that they were now in the charge of a stranger - a kind stranger, but still a stranger. Fast-forward to being picked up later at the school gate. "Did you give the flowers to your teacher?" - "No. And you went off and left me!" The children settled into their daily pattern of greetings and work, which Tony Jolley describes so well in his memories of the Infant School later in the decade. There was a morning and an afternoon break ("playtime") and of course a break for lunch ("dinnertime"). The school had no canteen and most children went home for dinner. Incidentally, nobody ever used the word "lunch". In the small light-industrial town which was Burton, the rhythm of life ran round four meals: breakfast, dinner (mid-day - the main meal of the day), tea (c.5.30pm - sandwiches or a snack meal like beans on toast) and supper (c.8.45pm - a small sandwich and a hot drink).

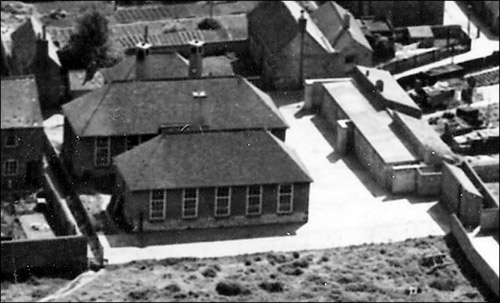

The Council Infants School had a yard but no playing field. The paddock-like field which was adjacent to the school (see above) belonged to Evans' Farm. In the photo above you can just see the faint detail of the railings which separated the playground from the field. Those railings made a delightful sound if you had a stick, held it fairly firmly at about waist height, and dragged it down the whole length of the railings. At the end of playtime and dinnertime, with all the children talking, playing, running etc, in the yard, there came the then-universal ritual. A teacher would appear and blow a whistle. All the children would freeze on the spot, as if suddenly playing a game of Musical Statues. There would then be a second blast of the whistle, and the children would scurry in silence to line up in their classes. It was always a matter of honour and status to be first in line. In the early 1970s, when educationalists - appalled at what they saw as totally unacceptable regimentation - did some research and asked children what they thought of this system, they were very surprised to be told that the children quite liked it. When asked why, the children replied that they liked it because if they kept their mouth shut and stood behind someone else, they couldn't get into trouble! On the west side of the yard were the air-raid shelters and the toilets - outdoor toilets of course. In the 1950s, only the staff had indoor toilets. The air-raid shelters were used for storage, and children were strictly forbidden to enter. In those more obedient, conformist days, no-one dared disobey. The boys' toilets were next to the air-raid shelter. They consisted of a black bitumen-painted concrete wall with a trough at the bottom, made up of those brown, salt-glazed, half-pipes. As a gesture to hygiene, a few small pale green cubes of disinfectant were occasionally scattered along the trough. There was absolutely no cover to these facilities, the smell on hot summer days and the unpleasantness of rainy days can be imagined ...... The girls had the relative luxury of a series of roofed cubicles, with a screen-walled access at the playground gate end (clearly visible in the photo above). The Council Junior School The day came when children moved up to the "Big School". Of course, they could see part of the Junior School girls' playground from their own playground, if they stood near the entrance to the girls' toilets; and many of them had walked through it if they used that route on their way to and from school. Further than that, very little was known about the other school, unless an older brother or sister had attended. In those days, Infant School children kept very much to their own school year age group as far as friends were concerned.

The school was of course much bigger than the Infants School, especially the playgrounds. That was the first big surprise: boys and girls were segregated at break times. The next surprise came when they found themselves divided into four "Houses" for sports and other competition purposes. There were no Houses at the Infant School. The Junior School Houses were named after trees, and each had its own primary colour: Fir (green), Oak (yellow), Elm (blue), Ash (red). This of course gave rise to a variety of rhyming taunts, eg "Fir and Oak are jolly good folk, Elm and Ash - potato mash!" (Fir and Elm could be swapped around in that rhyme, depending on your allegiance). For all work and achievements, the Housepoint system of rewards was used - only they weren't called House Points, they were "Team Marks". If work were of a good standard, it might be ticked when marked and the symbols "1 TM" or "2 TM" added to the tick. This meant that you had been awarded one or two Team Marks, respectively. Gradings like 2+1 or even 2+2 were used on special occasions (why not 3 TM or 4 TM? Was 2 the official limit and this an ingenious way round it?). Team Marks might also be awarded for neat writing, good behaviour, smart posture, and so on. Everyone had to register in a class book the Team Marks they had been awarded, along with the House they themselves belonged to. At the end of the week the Team Marks for each House would be added up and thus the total for each House across the school for that week could be worked out.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The next segregation came when you found out whose class you were in. What had been one huge class in the Infants School became two classes in the Junior School. All Classes were given a year number and a letter - in accordance with time-honoured tradition - as follows:

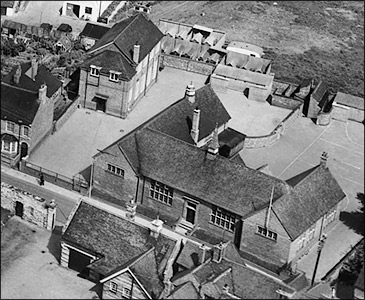

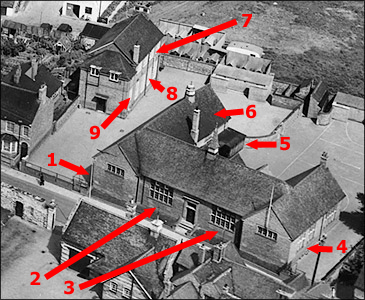

In fact, children often spent two years with Miss Stokes and then two years with Mr Norton, so classes 1X and 4X were sometimes split-year classes. All teachers have individual qualities, failings and quirks which make them unique. Miss Stokes was quietly spoken but quite strict. She occasionally took Music for all year 1 pupils, when, on top of all the necessary adjustments in the new school came the mortification of having to stand on the stage of the Hall in the first music lesson of the new school and sing - unaccompanied - in front of the entire year group, just to see what your voice was like. Those of you reading this and cringing at the memory - you can uncurl your toes now. On the other hand, if you were good, you stood a chance of winning an award at the annual Eisteddfod (music, reading and poetry competition). Miss Stokes was also quite slim - even gaunt. Unbeknown to most at that time, when eating disorders weren't really understood and nobody had even heard the words anorexia and bulimia, this was to have tragic consequences. Miss Leach was the other Year 1 teacher. Her classroom stood next to the headmaster's study in a separate building on the far side of the boy's yard (see diagram above). She never seemed to age very much over all the years she was there, but neither could you imagine that she was ever young. She was an ideal teacher of Year 1. She was kind, patient and thorough. She knew her stuff and she knew how to settle a class to steady work. As her classroom was next to the Head's room, children were generally careful to keep the noise down. If she left the classroom for a bit, and the noise levels rose, Mr Pentelow would often leave his office, open the classroom door and tell the class off.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mr White was well-liked and respected, being of a generally genial disposition. On the occasions when he did get angry, his lips would purse up and he would seem to swell as his face turned a delicate shade of puce. Apart from his other duties as teacher for Class 3, Mr White was in charge of boys' craft and football. Ah, the endless creations made from glue, cereal boxes, toilet roll centres, chicken wire, and paper mache - all painted with those powder-based paints. From such unpromising materials arose airports, stations, castles, prehistoric landscapes with dinosaurs - anything which had been chosen as The Project - to be exhibited with pride on Open Day. Mr Chambers had come to the school in the mid 1950s. He was by far the youngest member of staff, and played in local teams - cricket for Burton and football for Finedon. As is often the case with young teachers, he was liked and had a rapport with his pupils. He was at ease with them and had a good sense of humour; he was also a good teacher. He left in about 1960. Perhaps he felt that he would have more scope elsewhere: promotion prospects at Burton must have been limited, and even though he was a keen sportsman, he had no share in coaching the football teams; that was firmly in the hands of Mr White. Mr Pentelow was the headmaster. If other staff were absent, he would cover for them, but he also assisted Mr Chambers with class 4Y. This was in several senses the Top Class - it was the most senior class and it was sited on the upper floor of the building across the yard (see image above) and directly above his office. Silence prevailed when children went up and down the stairs. If it didn't and class 4Y were too excited, he would emerge from his office. Mr Pentelow was stern but fair, and often had a twinkle in the eye and a slight smile to the mouth. He liked and respected his schoolchildren but would tolerate no cheek or opposition. Not that he ever got much of that. His manner commanded respect. Sports Because the school had no field of its own, it had to use the Recreation Ground for Sports Day and football matches. Boys had to change in the lobbies at school and walk up to the Rec. The route then in use was to cross the road outside the school and walk to the corner of what is now the Tandoori takeaway but was then Barlow's Cake Shop. A smart turn to the left just past the shop led to an alleyway between the old farm buildings and No. 44 High Street. The alley is now blocked off, but the path used to lead across a couple of fields and then emerge at the corner of the Rec. The boys would march up there in pairs, with Mr White following, carrying a large hessian sack containing about six old leather footballs. Fair enough, until one remembers the football boots in use at the time. It wasn't until the end of the 1950s that moulded soles or screw-in studs were introduced. The football boot studs of the early 1950s were a series of half a dozen leather disks, attached to the sole of the boot by means of three short nails arranged in a triangular pattern. As you walked along the High Street, the nails in the studs made a loud and distinctive sound on the paving. Worse, prolonged walking on paving sharpened the ends of the nails and consequently inflicted cuts when they contacted an opponent's shin; also, the pavement walking eventually made the nails go through the sole, the insole, and into the bottom of your foot! Once a year, there would be the District Sports, which were always held at Highfield School in Kettering, which had an enormous field. The school would send teams, with only rare instances of success. Normal P.E. lessons took place in the girls' playground. The equipment was brought out of a black shed in the corner of the yard (no. 5 on the image above). In those far-off, pre-Nike days, standard school "gymshoes" were black close-woven nylon uppers, with a U-shaped elasticated top section. The soles were slightly ridged, light brown ginger in colour and made of a crepe rubber-like substance. If they were made by Dunlop, a horizontal diamond-shaped red and white logo appeared on the soles, on the part just ahead of the heel. For P.E., girls were told to take off their dress, or top and skirt, and they did P.E. in vest and knickers. Unimaginable nowadays. Boys with short trousers might be allowed to do P.E. in them, those wearing long trousers changed into shorts, which would have been brought to school in the obligatory P.E. bag - a large cloth bag with a drawstring. The bag would of course bear the child's initials - lovingly embroidered on by mothers. Boys might wear a vest, or else were bare to the waist - which was OK until they had to put on the coloured Team Bands which were made of a coarse, slightly hairy (possibly woollen) material which was infuriatingly rough and itchy on bare skin, and worse when the weather was hot. Other Annual Events Mention has to be made of the Class Christmas Pantomime and the Christmas Party. To ensure an equitable distribution of decent parts in the pantomime, the class would often be divided into two groups, which would perform on consecutive nights. On that night, despite strict instructions to ignore the audience, stay in role and remember your lines, the first priority when you got on stage was still to scan the sea of faces to try and see where your parents were sitting, to be followed by the also-banned smile and slight mutual wave. The Christmas Party was one of the highlights of the year. Children might be let out early at the end of the afternoon, so they could go home and get ready. They didn't have any "tea" at home because food would be provided at the party. Large children's parties in those days followed a similar pattern, whether they were school parties, Sunday School parties, or parties provided by the Working Men's Clubs. Long wooden trestle tables were set up, with paper tablecloths (bound to get soggy from spilt drink and jelly). Jellies were usually tinned peach or pear halves set in a sea of red jelly of indeterminate flavour (possibly raspberry). Sandwiches would be meat, chicken or fish paste (Shippams, anyone?) in thin ready-sliced bread cut corner to corner, so that it was triangular in shape. If the sandwiches had been prepared too far in advance, they would be starting to dry and curl upwards. Tea would be dispensed from very large, dark-brown enamel teapots. If it had been made too far in advance, it would be about the same colour as the enamel. Cakes of the sponge and sticky white icing variety were always on offer. Once the food had been eaten and the tables cleared, then games would begin. They were usually games of progressive elimination to music: musical chairs, musical statues, and a particular favourite: "Jumping the Mat". This game comprised two standard back-door coco mats set about ten yards apart and in line with one another. Boys and girls were paired off and, hand-in hand, had to go round in a large oval and jump the mat at each point of the oval. When the music stopped, the couple who had just jumped the mat were out. As the numbers reduced, one mat was removed, and the game continued until only one couple was left. They were declared winners. A large part of the attraction of the game lay in the opportunity to continually hold hands with a partner you liked, if you were lucky enough to get him or her as a partner. Other Memories Rainy Days Though in the mind's eye school days seem to have been one endless sunny summer term, obviously at times in the year there were days of bad weather. Teachers must have dreaded the declaration of a "Wet Playtime", with children confined to their classrooms and only a few at a time being allowed permission to go outside to the toilet. The lobbies had those old enormous cast iron radiators fed by large diameter pipes. Nonetheless, the internal scaling from being in a hard water area and the generally feeble nature of the system pump meant that the radiators were next to useless in giving out much heat. Also, the walls were painted with gloss paint in that shade of very light green generally known at the time as "eau-de-nil" ("Water of the Nile"? You've got to be kidding!). On rainy days, all those soaking wet, navy blue, belted gaberdine school macks just hung there without drying properly, and by morning playtime the accumulated condensation was running down those gloss-painted walls. The smell of that damp gaberdine was unforgettable.

Perhaps someone remembers all this and can send in a detailed account for us? It is a period and set of experiences which need recording. School dinners at that time did not rate very highly. "Tasty and appetising" often came a long way behind "nourishing and wholesome", but perhaps the place in Duke Street was an exception to the depressingly frequent national pattern of lumpy mashed potatoes with black bits in them, woody carrots, bullet peas, and the custard served from those large aluminium jugs. It had been standing a while and a thick skin had formed on top. If you were unlucky, as the custard was being poured onto your pudding, you got that thick skin as well!

Coveted Duties and Responsibilities In various classes there were little plum jobs which were coveted and prized for the status and the side-benefits: Ink Monitor, Milk Monitor, Bell Monitor, Tea Monitor, Post Monitor, Weather Monitor. Up to Class 2, you had to use a pen-holder and nib for all writing. Ballpoint pens were not in common use (and were not allowed in some schools for a number of years because they were thought to spoil children's handwriting). Felt- and fibre-tipped pens hadn't been invented, so it was a case of using a wooden pen-holder, a detachable nib, and dip it into real ink. Blotting paper was also essential if you wanted to avoid smudging. In Class 2, if Miss Clipson decided that your handwriting was good enough, you were then allowed to start using a fountain pen if you wished, but that was optional. If you wanted to carry on using a penholder and nib(s) then you could. Most children had a collection of different types of nib, acquired from Smith's paper shop. Every classrom desk had holders for the china inkwells, along with the horizontal groove which held pens and pencils. It was the Ink Monitors' job to replenish the ink in the inkwells via a large enamel jug. Apart from the perceived importance of the job, going and getting the ink meant getting out of part of the lesson. Until the early 1970s, school milk was provided free to everyone in education. The milk came in special sized bottles - one third of a pint, and was delivered every day to every school. It was the Milk Monitors' job to go and fetch a crate of milk for the whole class about 10-15 minutes before morning playtime - another opportunity to leave a lesson early. The Bell Monitor's job was to ring the school bell (if required) - a unique and very highly desired post. Tea Monitors got out of class just before morning playtime to bring the staff's tea and coffee from Miss Leach's classroom (which had a sink) to the Hall, where the staff would meet. There was no Staff Room. The Tea Monitors and the Bell Monitor were about the only children in school whose request to leave the classroom was readily - and often instantly - granted. The Post Monitor was another unique job, given to someone in the Top Class. In the 1950s, Burton Post Office was located opposite the school, in what is now the right-hand end of Barclays Bank. It was the Post Monitor's job to call in every morning just before school and collect all the mail for the school. The Weather Monitor was normally someone from Mr White's class. In the corridor just outside his classroom was the "weather board" - a large board decorated with a compass which had a rotating arrow showing the current wind direction. The board also gave other meteorological data, like temperature and an indication of the general wind speed. It was the Weather Monitor's job to read the thermometer and barometer, go outside and look at the weather vane on top of the former coach house opposite the school (it's still there!) to determine the wind direction, and also assess the strength of the wind. He or she then updated the arrow and the chalked data on the weather board, as well as entering the readings in an exercise book so that average temperatures, etc for the week or month could be worked out.

In the 1950s, girls and boys at Junior School didn't generally have steady boyfriends and girlfriends, respectively. Yes, there were people of the opposite sex who you liked, liked a lot, or even had a "crush" on. But that was about as far as it went. Love, if it can be called love, went largely unrequited. This may explain the huge importance of who you sat near, shared a group with, got as a partner in Country Dancing, danced with at the Christmas Party, and so on. It really mattered who you were with, and who you weren't with! Not only because of your personal preferences, but also because of the potential reaction of others in your class. Oh, the torment of having to dance with someone you really hadn't wanted to be paired with (will the music never end?), and then having your friends mention it later in the playground or on the way home, accompanied by the chorus: "We know you now!" in spite of all your denials. And maybe later the cold-sweat nightmare that your initials and theirs might appear in the middle of a love-heart pierced by an arrow, chalked on a public wall or fence where your parents might see it. In desperation, you'd be reduced to standing there, spitting on your hand, then frantically trying to erase the humiliating graffiti, for fear that otherwise there would be that hideous conversation with your parents - the one which started with the dreaded words: "What's all this about you .........."

Epilogue Yet for all the agonies and embarrassments, those were generally enjoyable days, certainly so when compared with the jungle of life at Secondary School which followed. The Junior Schools of the 1950s had a sort of timeless quality about them. The big national school building programme of the 1960s hadn't properly got under way. Our schools were brick and stone buildings which had stood there for the best part of fifty years or more. Our parents and grandparents had been taught in the same classrooms where we now sat. We had seen others pass through and now it was our turn. There was an unspoken but clear consensus throughout Society about what constituted Right and Wrong. Yes, children still went "scrumping" (raiding orchards), but no-one claimed it was all right to do it, even if you got away with it. There was still what was called then "a respect for other people's property". The country had come through a world war, victorious. It had been on its last legs but it was now recovering. There was full employment on a scale we can now only dream about. If school got out early at dinnertime and there were few people in the streets, you could go round to the factory and wait for the hooter to go. A side door would fly open and men wearing flat caps would pour out onto the street to go home for dinner. You could walk home with your dad. We have come a long way in the past fifty years, but we have lost a lot along the way as well. If this account has triggered memories of your own, please share them with us, however brief they are. Just e-mail in your memories and we'll add them to the special Reminiscence Page. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||