| Original article by Douglas Ashby 1999, transcribed by Margaret Craddock | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Until about fifteen years ago Harpurs Lodge, a remote farmhouse, stood at the end of All who knew Mrs Gilliat will agree she was a remarkable lady, very self-willed and strong of character. In those days it was hard to make a living on the Wold. At Harpurs Lodge water was never plentiful and the family had to rely on wells for their supply. A succession of dry summers and poor harvests brought the Gilliats almost to the verge of ruin and it was a familiar sight to see the cattle being driven down to Church Street to drink the cooling waters of the Stockwell, which stood against the wall opposite the former Church School. Fed by a spring, the pure stream was never known to run dry even in the severest drought and can still be heard underground to this day. In desperation the Gilliats gave notice to terminate their tenancy. Writing from Ugbrough in

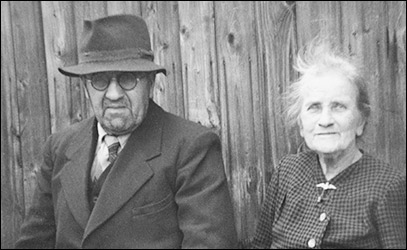

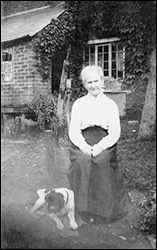

The Gilliats, later that year, moved into Burton Latimer and lived at No 1 Church Street which adjoined Osborne House, the former home of Dr and Mrs Kingsley, where they continued to supply milk and make butter and ice cream. Mr Gilliat died in 1926 aged 64 years but his widow, Sophia, lived on until 1956 when she died on September 7th, aged 92. Her eccentric son, William (Billy), lived with her and was a familiar figure in the town with his bicycle, which usually carried several buckets full of scraps for his pigs. Billy kept a small-holding in a field near the former A6 railway bridge which is now the site of the present A14 junction. Often misunderstood, son William was an interesting person to talk with but, above all, he was a great patriot. He fought for his country in the First World War and his poor, crippled feet bore witness to the fact that he had spent many hours in water-filled trenches. He died in 1968.

During her years at the Farm, Mrs Gilliat was careful to keep accounts of receipts and expenses and her books, beautifully handwritten, have been saved from destruction and provide a valuable record of the cost of living at the time. In 1899, coal cost £1 8s (£1.40p) for 1.5 tons. Seven shillings and tenpence ha’penny (40p) was paid for a stone trough. Three pigs cost £2 14s (£2.70p). You could buy a cow or even a pony for £10. Fourteen fowl were smothered, value 14s (70p) and a fox got 36 fowl at a value of £3. A pair of shoes for May cost 2s 11d (15p) and boots for William, 10s 11d (55p). A hat cost 7s 3d, a coat 14s 6d, gloves 9d, a blouse 2s and stockings 1s. Eggs sold at 1d each, that is just 5p a dozen! Milk was a penny ha’penny a pint, steak and beef 8d (3p) a pound and a pound of mutton would set you back fourpence ha’penny. Also, The Loss on the year’s working was £75 19s 4d (£75 96p). In 1903, Mrs Jacques, the Rector’s wife, paid £1 1s (£1.05p) for milk and cream covering the period July 19th to October 21st. On 1st January 1882, Mrs Gilliat wrote in her Victorian album this little verse:

|

|||||||||